A Personal Statement About Tradition

|

| The central library was burnt down in 2005 Image: David M Mayum from E-pao |

We are a product of our culture and traditions. But does it mean we have to conform to them forever and those cannot be changed at all?

Traditionalists are usually conservative folks, but as expected from the contradiction that defines contemporary Manipur, they can be hellish radical too.

For them, there is nothing above traditions, social mores and customs—not even the fragmented laws of the land. These social elements mould their world views; however, the meaning changes entirely in a political setting where there are armed movements, a strong current of revivalism and general mess induced together by the government, non-state actors and the civil society.

The Meetei Erol Eyek Loinasillon Apunba Lup (MEELAL) or loosely, the United Meitei Association of Language and Literature, demonstrates the duality of tradition crisply. It works for the revivalism of the Manipuris — specifically the Meitei’s tradition and culture and it is too politically incorrect to use the Sanskritised word ‘Manipur’ though I have used it here for convenience.

When we hear about these keywords related to traditions, we can imagine old folks who are so pious about the old ways, so religious that we can assume their world is as inflexible as their physical bodies. However, on 13 April 2005, the activists burnt down the central library in the heart of Imphal that officials estimated about 145,000 books with an amount pegged at 10 crores INR. Still it was no surprise seeing that, in this part of the world, both the government and the citizens never act before a calamity.

For that matter, the government gave in and introduced the use of Meitei Mayek (native alphabets) in schools. This write-up is not about judging MEELAL, which has been spearheading the campaign for the use of Meitei Mayek, but rather about the narratives of tradition.

From hindsight, we can tell it is a conflict between the past and the present. For three centuries, we have been overdosed with Hindu lifestyles while abstaining from the indigenous faith and value system. The wave of revivalism appeared in the first half of the 20th century but it was never clear.

For instance, in literature, we had this explosion of new forms of writing from the likes of Hijam Anganghal and Khwairakpam Chaoba and their ilk, though they wrote only in Bengali script. They succeeded the breed of writers who were infatuated with Sanskrit. It is notable that around the same time Naoriya Phullo established the Malem Apokpa Marup, circa 1930.

No one can deny it but the role of Meitei Mayek has been negligible until the last couple of decades, and now it is still in its formative stage. Nowadays, the campaign has changed to editing and deleting loanwords used in literature, theatre, film and music plus the use of the Mayek in every possible ways like signboards, vehicle registration number and the like.

As a whole, it is no wonder then how there is a thin, fine line between conservatism and radicalism. Perhaps this also explains how traditionalism is different, which is location- and people-specific, while conservatism is universal. Still it happens how the traditionalists can be so radical.

|

| Image: Anonymous ART of Revolution |

“The less there is to justify a traditional custom, the harder it is to get rid of it.”

― Mark Twain, The Adventures of Tom Sawyer

Once I went to one of my friends’ wedding, wearing a ‘khudei’, which was more of making my political statement than that of fashion. For the latter, we have this range of kurtas and pyjamas from the trendiest tailors yet I’d admit I have an allergy towards these clothes. It reeks of imitation, blindly following others’ culture and the others-are-better-than-ours mentality.

This is a bold statement from someone who sees tradition is more of a wall than a bridge.

Firstly, we live in such an uncertain age in an even more vulnerable environment; and secondly, the identity crisis is written all around us. Even the supposedly authentic traditions and cultures fail to be charming on one hand. On the other, there is always a doubt about the old ways, or of reviving the ‘real’ traditions and customs, because never have been traditions and cultures so great that those have remained unchanged over decades and centuries in any part of the world. Precisely the world is always changing and we need newer ideas more than we need some inherited customs.

If we look from another angle, there are two more reasons: one, in the existing social milieu the entire system is so rotten that insists us to find a new setting; and two, it is a form of rebellion against the currents of our time. Amidst this bleak condition, there is some solace in tradition.

Despite the yearning for new ways of life, it is good to see that some of the old ways persist—for example the acquired religion of Hinduism failed to mar the Lai Haraoba festival and weaken the role of women in socio-economical and political aspects. In a way, the proposition is to replace the existing condition with a humanitarian lifestyle rather than going back to the past and frankly, if it is asked how, I have no clear answer except this hypersensitivity to both the present and the past.

Traditionalism is also a big turnoff because of its mutuality with religion. For an atheist, it would be like sleeping with a literal goddess under a wet blanket on a chilly December night—whatever it means. Besides, the rigid rites and rituals make the going harder. For a nonconformist atheist, replace that goddess with a deity of disease. The math is simple but that circumstance is not! Yet the whole issue is not about the killing gods or of having an anti-establishment inclination.

Suppose the traditionalists with somewhat radical thoughts have reached their destination—in the case of Manipur, say, everybody has learnt Meitei Mayek; we have retained the old name ‘Kangleipak’; everybody is back into the fold of Sanamahism, and so on—then it is quite apparent that the conditions will certainly become static, for the simple reason that traditionalism encourages only protection and preservation of the values, beliefs and customs and transferring these elements to the next generation.

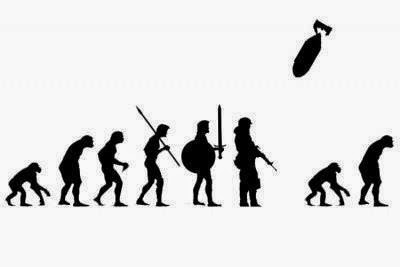

In the words of Franz Kafka, every revolution evaporates and leaves behind only the slime of a new bureaucracy. It will be sheer foolhardy for the traditionalists to keep on believing that we are at the centre of the universe, when in reality the vacuum created by their ideologies based on myths and legends is the cause of the call for new ways of life.

|

| Image: Anonymous ART of Revolution |

Tradition is against the law of nature. We know nothing is permanent in the universe. There is a silver lining, however, for the pro-rigids. In addition to popular rule, the factors of tradition, economy and bureaucracy organise a society. From a pragmatic standpoint, this seems true because most of us are believers and followers and nobody wants to be called an outcast.

It is truer in our society where community living is a way of life and what the others (read relatives and localities) think about us is as important as the daily plate of rice. Overlooking the traditions would be like a request for a ticket to the land of ‘Loi’ and ‘Yaithibi’. However, in our generation, when the Loi’s Andro is now a centre of cultural significance as well as producing one of the best local drinks, the concept of excommunication has lost its essence in this context. Social exclusion sounds terrific, in fact, considering the filth and dirt that stain the dominant society.

Does tradition provide any hope in our existential problems? Giving in to a higher power is one thing, knowing the essence of our existence is totally a different story.

As mentioned earlier, we are in a pit of identity crisis. Ironical because we always show this racial and ethnic identity before anything;no matter how we are conscious about it during the times of tribulation. The most obvious example is in the cases of racism and other forms of discrimination that we face frequently in other parts of India, where there are altogether different concepts of race, caste, creed and identity.

Certainty and rhythm create tradition but again in my native place, the sum is creating barriers with the obvious un-rhyming beats. The predominating parochial outlook allows no room for discussion. The condition is more horrible on ground zero. We do find some consolation in abandoning the customary practices like drinking the water from a tub in which a pundit had dipped his feet.

Presently, we also have a tradition of killing in the most brutal ways on the flimsiest grounds.

|

| Image: Anonymous ART of Revolution |

Except for some fortunate folks, many of us are confused about our nationality and religion. The prevailing milieu, which manifests in the reigning gun culture, institutionalisation of corruption and violence and enduring ethnic strife, only adds insult to injury.

In the form of a saviour, now and then the traditional faith and living style, plus the political and personal thoughts comfort us; however, we know clearly that things are as bleak as ever. In a way, tradition is a potential game changer but it has more loopholes than steps that we desperately need to walk on. Tradition is outdated; it is synonymous to chains and fetters; and it commands obedience and loyalty without any question. The more it shows the less there is rationality.

As with religion, traditions share a close affinity with culture; sometimes they are used as synonyms. This might offer solutions to get rid of the identity crisis but as always, nothing is clear. Take the case of rich folks in the valley who worship Sai Baba. People have gone to the extent of burning down a library but the adversaries are galore.

For the activists and worshippers alike, the issue might be exclusive, however when we look at it taking a couple of steps backward, the big picture is a huge confusion with everybody claiming they are right and nobody knowing who is wrong.

I admit life is not possible without tradition. It strengthens connection between people. It helps us in surviving in the animal kingdom. We are the creatures of habit and always have a yearning to identify ourselves with a larger group. In a way, it is not an option—we are born with it and we will die with it. The necessity is apparent from those people who would convert to a foreign religion to have a sense of belongingness amongst many other reasons.

Remember the character of Tevye in the classic ‘Fiddler on the Roof’. He uttered: ‘Traditions, traditions. Without our traditions, our lives would be as shaky as... as... as a fiddler on the roof!’

Contrarily we fear that we might be excluded. Despite these implications, the only way out of the prevailing unrest is to try new things, new positive things. Give a break to the old ways. Though we know tradition binds people, the case is entirely different in our hometown, with one group hating another. Alternatively, how about learning other traditions and cultures to have a broader world view?

To conclude, if we have to be in cahoots with traditions, we might as well be accepting the gross injustice in our private and public lives.

“Tradition becomes our security, and when the mind is secure it is in decay.” ― Jiddu Krishnamurti

Comments

Post a Comment