The Ghosts of 1962

The state as a person of international law should possess the following qualifications: a ) a permanent population; b ) a defined territory; c ) government; and d) capacity to enter into relations with the other states.

—Article 1, the Montevideo Convention on the Rights and Duty of States

|

| British Indian Empire 1909; Imperial Gazetteer of India |

During the 1962 Sino-Indian War, Jawaharlal Nehru wailed on the All India Radio how Zhou Enlai had grabbed and bitten his ass badly. That was after withdrawing his soldiers and calling all of them, all the way back to Bengal: the last frontier of mainland India. We have known the motives of Indian leaders from day one when the great democracy annexed states like Manipur in 1949 but not many of us know how they would leave the Northeast to its own devices in trying times. Some may argue that it happened a long time ago and that we should move on because today India is growing at 20% economically. Yes, ideally it would be but China’s victory in that war has been more political than military and the entire fiasco has much significance in contemporary politics.

India’s modern history is half complete without a reference to the 1962 War that was fought from 20 October to 21 November. Another term that describes the war, the Sino-Indian Border Conflict, denotes the basis or rather madness on which the war was fought between the supposedly future superpowers. In India it was the Bhārat-Chīn Yuddh and in China the Zhōng-Yìn Biānjìng Zhànzhēng. It might imply nothing to many people because it implies, so to say, nothing beyond having a chapter like the Siachen’s on textbooks for schoolchildren; yet there are some narratives that will ever matter to the Indian political system for reasons good or bad. For instance, last year, the Indian external affairs minister, Sushma Swaraj, revealed that the row over China granting stapled visas to the Indians from Arunachal Pradesh are yet to be resolved. Like on an individual level, unresolved issues can cause long-term negative effects for a nation.

So, China has been granting visas to Arunachalis claiming that these people, who look more like them than Indians, and the territory of AP are theirs. Unsurprisingly, India has been expressing its displeasure while covertly teaching the Arunachalis to speak Hindi like a farmer from Uttar Pradesh: in a rustic yet unpolluted language. I’d say we become a people with over-sized tongues suddenly whenever it comes to Hindi because of our linguistic proximity to Austroasiatic, Sino-Tibetan, Tai-Kadai, Tibeto-Burman and other such ‘un-Indian’ languages.

Nevertheless the claim for people and territory was also one of the main reasons why the war broke out five decades ago. A more complete story can be traced back to 1914 when the then British India signed the Simla Accord with Tibet and drew the 890-km long McMahon Line, which the present-day India fully endorses while China has been vehemently opposing it. For the latter, Tibet, or South Tibet to be precise, has no sovereignty; hence the non-validity of the line and the assertion that the demarcation should be in accordance with the Line of Actual Control. Further earlier, the circus had begun in the late 19th century between British India and the Chinese.

The disagreements over Johnson Line and Macartney–Macdonald Line are also fine examples. If we dig deeper we will only find that the issue is a creation of the colonialists, who kept changing their borders and territories according to their requirements from time to time.

It is hard to support the Tibetan cause politically with India’s self-interest motives and the American monkey business. Meanwhile, India could have avoided the war by making a few compromise and taking some proactive actions on Aksai Chin or elsewhere but it was too greedy to get rid of a land—where ‘not a blade of grass grows’ according to Nehru, and he was actually the leader who started the war regardless of India’s pathetic capability for a fight. Besides the greed, it was too incompetent to challenge another country but it did and paid the price for it. It did not only lose only Aksai Chin but also created a room for disagreement on the erstwhile North East Frontier Agency, again named and created by the British out of an undefined portion of Tibet and which today exists as the province of Arunachal Pradesh, where Hindi is more popular than Asa Akira or its supreme leader of the quarter of a land known by the name of Kiren Rijiju.

In schools we were brainwashed with a very different political map of India, which shows Gilgit-Baltistan (or Pakistan-Occupied Kashmir) and Aksai Chin (or Hotan Prefecture in the Chinese autonomous region of Xinjiang) as a part of India. It would not be a shocker if people in India still trust in that lie. Cartography can be such a bitch for all we know and we have as well seen recently in the JNU case on how the masses can go crazy over the abstract idea of an ‘imagined community’ that we love to call a nation. Like the utility of cartography for schoolchildren, we were taught about the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence or the Panchsheel Treaty of 1954 between India and China.

|

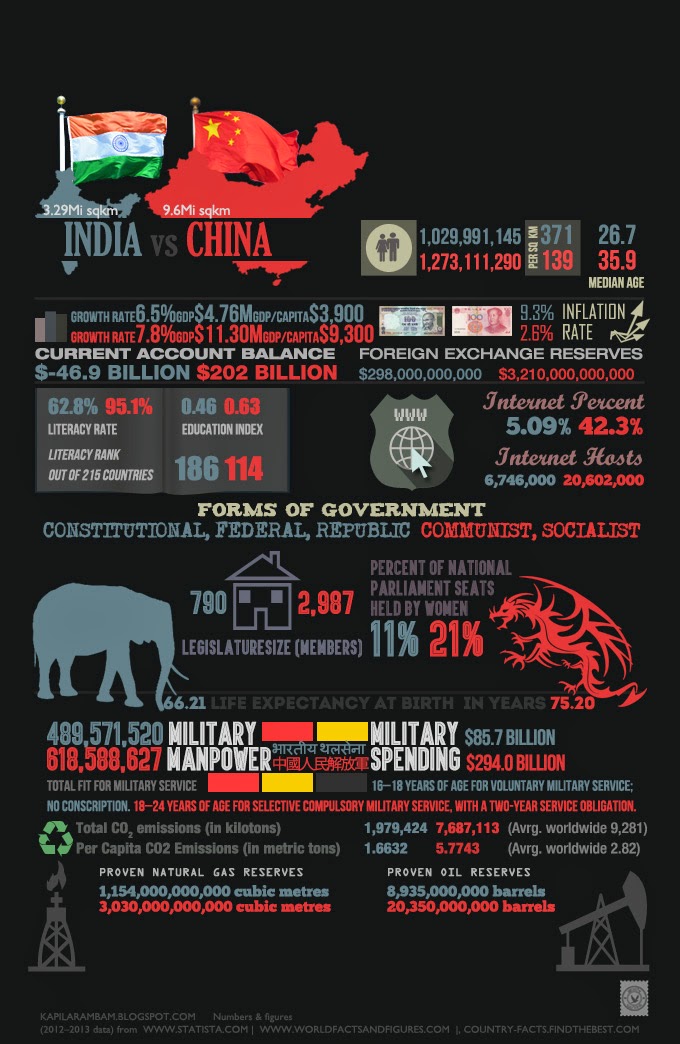

| A graphic from 2014 |

The first decade of Indian independence from Britain was spent on building and deliberating on so many other things except for the nation’s understanding of its own territory. However, the landscape started changing in 1954 when China produced a map, which more importantly showed the boundary of Hotan Prefecture. The Indian government reacted with a deafening silence while on occasions humming the out-of-tune Hindi-Chini Bhai-Bhai. It was all quiet until a couple of years later when the CIA also started recruiting Tibetan rebels using the Indian territory and later when news broke about China building roads ‘inside’ India in Hotan Prefecture aka Aksai Chin. The rest, as they say, is history.

When the Nehru government professed about the ideals of ‘the enemy of an enemy is a friend’ by offering a home and an address for the Dalai Lama in 1959, things had reached their saturation point. Nehru even put his defence minister, VK Menon, out of the communication loop because the minister, a communist who might be loyal to China, cannot be trusted. Without caring a hoot about the expenditure, the Nehru government started sending his troops to the border areas under a fancy project of ill-conceived Forward Policy which triggered the war. However, today, we know there was not even a support like the AFSPA to save the government-sponsored gunmen, leave alone put up a fight in a battle. Then it is just natural how mainland Indians are cursing both their favourite prime minister and his questionable foot soldiers consisting of generals, brigadiers and dogs and others till today.

China won the war—storming up to Tezpur—but retreated because it had achieved its objective of claiming the South Tibet territories while humiliated, India learnt a lesson or two about international border and how a petty territorial dispute can turn into a war. But India is yet to realise that the entire Northeast is not under the Chinese threat so much as the raging armed conflicts that it chooses to describe as low-level internal affairs and ignores them. Well, it might be a good propaganda material to further brainwash us about China but India needs to understand that there are also expressions like, amongst others, life, freedom and emancipation.

Besides, learning a truth about international border is not the end. The ongoing territorial disputes all over its border areas, from Pakistan to Burma, should be a lesson in itself but it seems the Government of India is waiting and watching for a crisis that would forcibly waken it up. For that matter, the border dispute with China is still far from over; and if this was not enough, the sanctuary of the Dalai Lama in India is no less than a netherworld for China. Incidentally the revered monk is scheduled to visit Arunachal Pradesh in November 2016.

And remember Neville Maxwell, the Australian journalist who had revealed some meat that most Indians found it hard to bite. For clarification it was not beef meat but a confidential report of the 1962 war. In the aftermath of the border conflict, for the first time, nationalists and even people with learning disabilities in mainland India discovered that they have a group of countrymen but who don’t look them, who don’t eat like them and who don’t exist like them. And the process of understanding this issue is still a work-in-progress matter. In another word, the Northeast had appeared for the first time, though with no clarity, in the national imagination of India. In some places like Manipur and Tripura, the Indianisation process had started centuries earlier thanks to the Hindu missionaries.

After 1962, on several occasions the two Asian neighbours have been involved in the same border skirmishes albeit with comparatively lower intensity: 1967, 1975 and 1987 and further into the new millennium. One of its effects is the heavy militarisation of Indian borders, some of which like that of Manipur’s that has nothing to do with the two countries’ tendency to poke nose into each other’s affairs. There is little chance that the issue will stop haunting New Delhi and Beijing in the near future, though on economic matters, the two of them have been making some good progress.

- Concluded.

Comments

Post a Comment