‘The Smell of Man’ As an Act of Poetry

The Smell of Men – Selected Poems

Publisher: Red River (22 August 2021)

Language: English

ISBN-10: 8195305601

ISBN-13: 978-8195305605

|

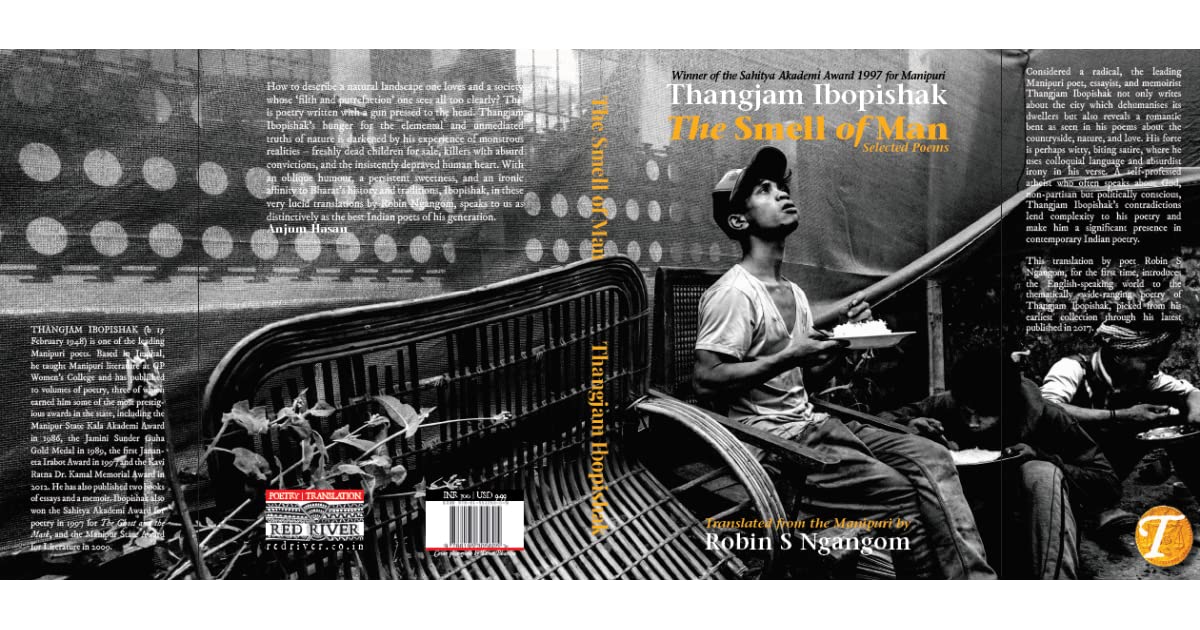

| Image: Amazon |

According to translation theorist James Holmes, all translation is an act of critical interpretation, but there are some translations of poetry which differ from all other interpretative forms in that they also have the aim of being acts of poetry. This description best captures the recently published The Smell of Man, Selected Poems by Thangjam Ibopishak and translated by bilingual poet Robin Ngangom.

Comprising 47 poems originally written by acclaimed writer Thangjam Ibopishak who writes in Manipuri/Meiteilon, The Smell of Man as an act of poetry introduces the English-speaking world to his thematically wide-ranging poetry, which has been translated by Ngangom, who considers that Ibopishak writes about a city that dehumanises it dwellers.

In his foreword to the book, poet and cultural theorist Ranjit Hoskote wrote, ‘The Small of Man is wonderfully timely and welcome book. The political is omnipresent in these poems, which are attuned to the everyday emergencies of heavily militarised North-eastern India.’

Hoskote added, ‘(Ibopishak) refused to be constrained within a regional identity prescribed from the outside. His is an anchored and robust cosmopolitanism, which takes delight in plural artistic ancestries, finds rapture in the work of colleagues elsewhere…Ibopishak locates himself in a redemptive and replenishing multilingualism.’

An associate English professor at the North-Eastern Hill University in Shillong, Ngangom has published individual poems by the same poet, and a few of them are in many undergraduate English lit syllabi across mainland India. Yet this book, which is his fourth, is the first full-fledged collection of translated poems that is, in his own words, ‘mostly autobiographical, written with the hope of enthusing readers with my communal or carnal life — the life of a politically discriminated against, historically overlooked individual from the nook of a Third World country.’

We will need a context to understand his statement. Often misrepresented or underrepresented, not only the literature from India’s Northeast has been so much stereotyped but also the very term ‘Northeast’ is under scrutiny for two reasons: one is the fact that it is a colonial construct, and two, the region has diverse ethnic groups and communities having no common history or heritage. Clubbing all the kinds of literature under one head called the Northeast writing, which people usually do, will be no different from putting various fruits in a basket and calling it just one name.

Both the poet and the translator hail from Manipur, where you can locate its literature. It was once a kingdom that became a part of British India in 1891 and further merged controversially into the union of India in 1949. This merger has been long considered to be the genesis of insurgency and the armed movements for the right to self-determination. The area also witnessed some of the fiercest battles during the Second World War.

In the post-war period, when existentialism was gaining currency elsewhere, there was a group of poets in Manipur, who, according to Ngangom, ‘began responding to the altered circumstances by breaking with their romantic predecessors and choosing a diction that will suit their times.’ Ibopishak, who was born in 1948 and taught Manipuri literature at the prestigious GP Women’s College in Imphal, belongs to this group of poets with newer lived experiences in a comparatively new socio-political system but fraught with violence, militarisation, underdevelopment, and identity crisis.

A decade or two before the war, Manipuri literature was influenced by romantic works with major contribution by the triumvirate of Khwairakpam Chaoba, Dr Lamabam Kamal and Hijam Anganghal.

Then, one of the most prominent poets to emerge after the war is Thangjam Ibopishak. Here it is noteworthy that the translator is also an eminent writer in English to have occupied a spot in the list of writers who write in English that is completely different from the category of writing that many people refer to as Indian English Literature or Indian Writing in English.

According to the translator, the writer is a master of colloquial language and absurdist irony, and is as well the ‘quintessential irreverent, self-professed non-believer, and expletive-loving non-conformist.’

One of the takeaways is that Ngangom has reproduced with such workmanship in this book and in a method that we can describe as direct-access-to-the-original style and is also syntactic and structural in nature. The translator has broken through the border of language without losing much in transcending a language fence, which is considered to be an original sin in translation.

American poet and translator Maia Evrona expresses that there are usually two kinds of readers when it comes to books in translation. The first type is the reader who never considers the existence of a translator, and who will heap all blame or praise upon the writer alone. The second type is the reader who will remain convinced—no matter how engaging a particular translated book may have been—that he or she has been cheated by the translator and by the very fact of reading in translation. For that matter, there is always a danger of translated poems becoming wooden and uninspiring but rest assured, with The Smell of Man, there will be a third type of readers, who will be interested in the relevance of both the writer and the translator.

The success of this book lies not only in the imaginative reproduction of wit and satire, as evident in poems such as ‘I Want to be Killed by an Indian Bullet’, ‘Gandhi and Bullet’, ‘Bluebottle Fly’ and others, but also in the creatively parsimonious use of words and expressions that expresses so much meanings in so few words. The ‘robust cosmopolitanism’ in his poems implies that anybody interested in poetry will be able to relate to Ibopishak’s works, even easier because it’s written in a colloquial style. Above all, Robin Ngangom has done an admirable job, making the Manipuri works easily accessible. We can also safely conclude that all these translated work in The Smell of Man is an act of poetry. To complement, the book also includes an interview of the original Manipuri writer.

This review was originally published in Together, a national family magazine, in its October 2021 edition.

Comments

Post a Comment