Mounao Thoibi’s Heartache: On Watching Manipuri Cinema

The literal meaning, for the want of an exact word in English, would be too funny, however ‘mounao’ implies a young housewife — albeit, with a disparaging tone because of the age. In Mounao Thoibi (2013), Bala plays Thoibi, a mounao, in which she gets married when she is in IXth standard: that is roughly when she is around 13–14-year old. That’s the beginning of the problem. Spoiler alert: It is not the age factor, but rather the entire treatment of the film. It shows everything that is messed up in the present Manipuri film industry too.

Mounao Thoibi is interesting, on one hand, because it shows a part of our social reality. The only problem is that, like in our real patriarchal society, the film exposes the ills, but from the perspective of someone who unquestioningly conforms to that kind of system.

First half

No known maichou had spoken on this particular issue but a long time ago in faraway Greece, Diogenes despite his cynicism and despise for social conventions, had preached optimistically that the foundation of every state is the education of its youth. The people behind the making of Mounao Thoibi seem to have taken this saying to heart. However, sans any rationality, they have equated youth to the girls. Therefore, it is Thoibi’s main duty to take care of herself. At one point, it appears as if it will bring about a revolution if she performs her duties well. If not, she can blame no one but herself and has to take all the responsibility for any misfortune. It took several male protagonists, including the lead actor, his father, his two friends plus Thoibi’s father and one of her seniors to prove that point!

Before her marriage, Mounao Thoibi is a girl-next-door type, studying in a local high school. She belongs to a typical middle-class family. Her mother is indulgent and her father is everything that the mother–daughter duo is not. In a tedious narrative, we see that one of Thoibi’s seniors loved her secretly though she would tell her friends that he was just a kid. An axe was already placed over her head in the earlier part of the film. The reason was that she had been born as a girl.

It started with Feijao (Bonnie) who played a timid bachelor, who stayed so timid during his first ‘unaccepted’ marriage, but by a miracle, he became almost a like a real hero in his second marriage — though only for a fraction of time before the conclusion of the film. He is so strong in the end that he can even ignore his former life support, Mounao Thoibi, while he leaves for his wedding feast. Earlier Feijao used to live with his widowed father — they take turn cooking and running errands for the family — and he has two close friends, Bormani and Manihar who are a fine example of bad actors.

The two buddies have been searching for a girl for Feijao but he has been so finicky when it comes to girls, in spite of his advancing years. He was nearly 40 when circumstantially he and his friends saw Thoibi going to school with a couple of her friends one fine day.

If you fast-forward the movie for half an hour, you will hardly miss anything.

In one of the scenes, Thoibi’s father scolded her that she and her mother do not watch any meaningful television shows. Ironically, while this film is intended to be informative, it fails miserably, despite the efforts put up by some of the characters, who fool around simplistic plots. Still Feijao gets a complete image makeover in the denouement and Thoibi is drowned in her tragedy but like other mediocre films, it lacks any grip to capture the viewers’ attention. It does succeed, overall, in one area: spreading male chauvinism.

Intermission

Boys can chase girls, court them, impersonate as an officer to woo them and do anything possible, but for the sake of repetition, a girl does not have the privileges nor she can even think about them. Otherwise they will face the same fate as Mounao Thoibi. She was left to her own devices because she was a woman. The moralistic conclusion in this film is more miserable than the light Hindustani music used as the score, which is again a blend of hardly inspiring composition and rip-off from who-knows-where.

Generally, cinema has two roles: to entertain and to inform. Manipuri cinema has a third role: to irritate. It is a wonder how acclaimed filmmakers can ‘manufacture’ this kind of a biased and shallow movie. Audiences have every right to interpret the movies in their own ways. First, the filmmakers do not bother how much they would test our patience, producing half-baked films that are passed off as entertainment products — and some of them like Mounao Thoibi as infotainment. In most cases, you cannot watch a Manipuri film beyond a point because it is so pathetically ridiculous. This happens in the bulk of the 30–40 odd films that are produced annually in the local film industry.

People in the industry would argue that the stars and filmmakers are doing us a great favour. They have been making films in a limited market, with limited technology and resources, and with a surety for limited returns on their investment. Once a filmmaker in my locality explained it to me. The taste and choice are personal. People in other far-flung areas would cry watching these flicks. Excuse me.

Film industry in Manipur after going digital is in its formative period. We had had the first celluloid film, Matamgi Manipur, back in 1972, but the new thrust occurred — only with the advent of digital films in the late 1990s and early 2000s — after the banning of Hindi entertainment that used to be ‘imported’ from mainland India.

We can say this digital film industry was an artificial start rather than a natural evolution. As mentioned, more than the experience, the limited market poses a huge stumbling block. This cannot be, however, the excuse for producing cheap, meaningless movies year in and year out. If external factors are justifications, watch one of the latest movies, Locke, the British drama released in the same year as Mounao Thoibi, and which entirely consists of scenes taken inside a car. Even the gigantic Bollywood is very weak except in a few selected genres like family dramas and parallel films.

Manipur film industry has the potential to excel in some areas. Unfortunately, likable films are so rare. We can only name Mami Sami, Nongallabasu Thaballei Manam and Phijigee Mani out of the lot. By the way, the duration of the hugely popular Phijigee Mani can be shortened to a half because the storyteller considers the audiences have wits so little that he has to repeat the narrative too much using flashback every 10 minutes in the 110-minute long film; but then, it is a superhit!

Second half

Cinema enthusiasts have a plenty of expectations from the creative film folks. But till today, the entire industry is almost a monopoly of the legendary Aribam Syam. Ever since the release of Lamja Parshuram in 1974, he has been the only visible face in the industry. In the last decade, we have seen many aspiring and talented filmmakers but they are mostly struggling, not with their medium of choice but the process of making good cinema.

We are living in such a critical juncture of civilisation but conformity and unquestioning artistic approach have only added a veil to the already bleak milieu. This lies stark because even if someone makes a film on the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act, s/he does not hesitate to compromise the political stand of making such a film. It appears as if mere acceptance, regardless of the authority or institution, is the end of creative pursuits. Yet this shallowness only demeans the efforts they have been putting up on their works.

Perhaps we only have to wait for their creative juices to flow in the future. Films like Mounao Thoibi can be made more realistic. It is considerable because we do not have the issue of child marriage, but we live in a world where family planning is an alien term. Still we do know how to appreciate a good movie.

Concluded.

The Directorate of Film Festivals is organising a three-day festival of cinema from the region — Fragrances from the North East — at Siri Fort Auditorium complex in New Delhi from August 22.

Mounao Thoibi is interesting, on one hand, because it shows a part of our social reality. The only problem is that, like in our real patriarchal society, the film exposes the ills, but from the perspective of someone who unquestioningly conforms to that kind of system.

First half

|

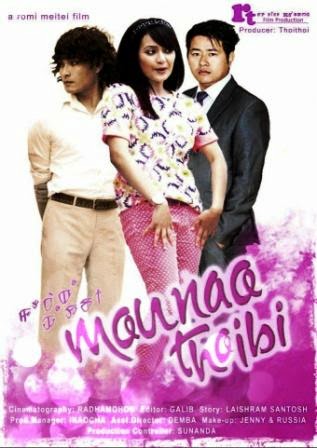

| Image: Adapted from the official Facebook page of the film, Mounao Thoibi |

No known maichou had spoken on this particular issue but a long time ago in faraway Greece, Diogenes despite his cynicism and despise for social conventions, had preached optimistically that the foundation of every state is the education of its youth. The people behind the making of Mounao Thoibi seem to have taken this saying to heart. However, sans any rationality, they have equated youth to the girls. Therefore, it is Thoibi’s main duty to take care of herself. At one point, it appears as if it will bring about a revolution if she performs her duties well. If not, she can blame no one but herself and has to take all the responsibility for any misfortune. It took several male protagonists, including the lead actor, his father, his two friends plus Thoibi’s father and one of her seniors to prove that point!

Before her marriage, Mounao Thoibi is a girl-next-door type, studying in a local high school. She belongs to a typical middle-class family. Her mother is indulgent and her father is everything that the mother–daughter duo is not. In a tedious narrative, we see that one of Thoibi’s seniors loved her secretly though she would tell her friends that he was just a kid. An axe was already placed over her head in the earlier part of the film. The reason was that she had been born as a girl.

It started with Feijao (Bonnie) who played a timid bachelor, who stayed so timid during his first ‘unaccepted’ marriage, but by a miracle, he became almost a like a real hero in his second marriage — though only for a fraction of time before the conclusion of the film. He is so strong in the end that he can even ignore his former life support, Mounao Thoibi, while he leaves for his wedding feast. Earlier Feijao used to live with his widowed father — they take turn cooking and running errands for the family — and he has two close friends, Bormani and Manihar who are a fine example of bad actors.

The two buddies have been searching for a girl for Feijao but he has been so finicky when it comes to girls, in spite of his advancing years. He was nearly 40 when circumstantially he and his friends saw Thoibi going to school with a couple of her friends one fine day.

If you fast-forward the movie for half an hour, you will hardly miss anything.

In one of the scenes, Thoibi’s father scolded her that she and her mother do not watch any meaningful television shows. Ironically, while this film is intended to be informative, it fails miserably, despite the efforts put up by some of the characters, who fool around simplistic plots. Still Feijao gets a complete image makeover in the denouement and Thoibi is drowned in her tragedy but like other mediocre films, it lacks any grip to capture the viewers’ attention. It does succeed, overall, in one area: spreading male chauvinism.

|

| Image: Adapted from the official Facebook page of the film, Mounao Thoibi |

Intermission

Boys can chase girls, court them, impersonate as an officer to woo them and do anything possible, but for the sake of repetition, a girl does not have the privileges nor she can even think about them. Otherwise they will face the same fate as Mounao Thoibi. She was left to her own devices because she was a woman. The moralistic conclusion in this film is more miserable than the light Hindustani music used as the score, which is again a blend of hardly inspiring composition and rip-off from who-knows-where.

Generally, cinema has two roles: to entertain and to inform. Manipuri cinema has a third role: to irritate. It is a wonder how acclaimed filmmakers can ‘manufacture’ this kind of a biased and shallow movie. Audiences have every right to interpret the movies in their own ways. First, the filmmakers do not bother how much they would test our patience, producing half-baked films that are passed off as entertainment products — and some of them like Mounao Thoibi as infotainment. In most cases, you cannot watch a Manipuri film beyond a point because it is so pathetically ridiculous. This happens in the bulk of the 30–40 odd films that are produced annually in the local film industry.

People in the industry would argue that the stars and filmmakers are doing us a great favour. They have been making films in a limited market, with limited technology and resources, and with a surety for limited returns on their investment. Once a filmmaker in my locality explained it to me. The taste and choice are personal. People in other far-flung areas would cry watching these flicks. Excuse me.

|

| Image from Imp Awards |

Film industry in Manipur after going digital is in its formative period. We had had the first celluloid film, Matamgi Manipur, back in 1972, but the new thrust occurred — only with the advent of digital films in the late 1990s and early 2000s — after the banning of Hindi entertainment that used to be ‘imported’ from mainland India.

We can say this digital film industry was an artificial start rather than a natural evolution. As mentioned, more than the experience, the limited market poses a huge stumbling block. This cannot be, however, the excuse for producing cheap, meaningless movies year in and year out. If external factors are justifications, watch one of the latest movies, Locke, the British drama released in the same year as Mounao Thoibi, and which entirely consists of scenes taken inside a car. Even the gigantic Bollywood is very weak except in a few selected genres like family dramas and parallel films.

Manipur film industry has the potential to excel in some areas. Unfortunately, likable films are so rare. We can only name Mami Sami, Nongallabasu Thaballei Manam and Phijigee Mani out of the lot. By the way, the duration of the hugely popular Phijigee Mani can be shortened to a half because the storyteller considers the audiences have wits so little that he has to repeat the narrative too much using flashback every 10 minutes in the 110-minute long film; but then, it is a superhit!

Second half

Cinema enthusiasts have a plenty of expectations from the creative film folks. But till today, the entire industry is almost a monopoly of the legendary Aribam Syam. Ever since the release of Lamja Parshuram in 1974, he has been the only visible face in the industry. In the last decade, we have seen many aspiring and talented filmmakers but they are mostly struggling, not with their medium of choice but the process of making good cinema.

We are living in such a critical juncture of civilisation but conformity and unquestioning artistic approach have only added a veil to the already bleak milieu. This lies stark because even if someone makes a film on the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act, s/he does not hesitate to compromise the political stand of making such a film. It appears as if mere acceptance, regardless of the authority or institution, is the end of creative pursuits. Yet this shallowness only demeans the efforts they have been putting up on their works.

Perhaps we only have to wait for their creative juices to flow in the future. Films like Mounao Thoibi can be made more realistic. It is considerable because we do not have the issue of child marriage, but we live in a world where family planning is an alien term. Still we do know how to appreciate a good movie.

Concluded.

|

| “Nostalgia: The Greek word for ‘return’ is ‘nostos’. ‘Algos means ‘suffering’.” — Milan Kundera Image from Sunday Matinée |

Breaking News

The Directorate of Film Festivals is organising a three-day festival of cinema from the region — Fragrances from the North East — at Siri Fort Auditorium complex in New Delhi from August 22.

|

| For details, visit http://www.dff.nic.in/moreof_northeast.html |

The story is relevant to a section of our adolescent population but the quality is very poor in terms of script writing and acting.

ReplyDelete